Cashless Systems Accelerate Inequality

By Frane Maroevic, Director General, International Currency Association

For years, tech platforms and card companies have framed the drift towards cashless payments as an inevitable march into a sleeker future. The pitch was seductive: tap, go, forget the rest. But a closer look at what that shift has produced — who wins, who loses, and who gets locked out altogether — tells a different story.

At the centre of this transformation is a simple yet uncomfortable reality: moving from cash to card or mobile payments replaces a universal, publicly governed system with privately owned infrastructure whose logic is profit, not access. And when payments become a revenue stream, inequality follows.

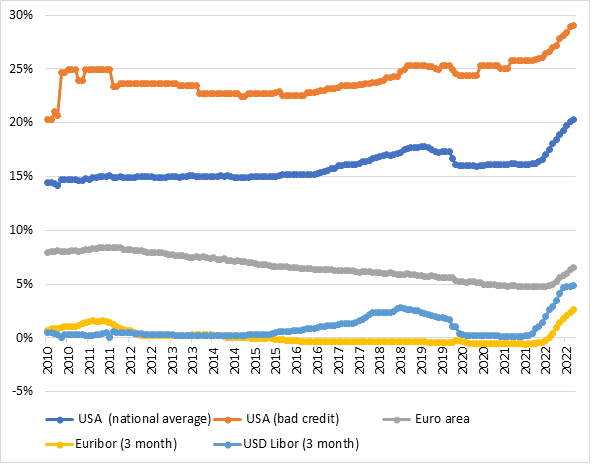

The scale of this shift is best captured in the trajectory of credit card interest rates. In an article by Barbara Brandl, a key graph (Figure 1) shows, US credit card APRs climb steadily from 2010 onwards, rising far above European equivalents. While Eurozone overdraft rates hover around 8%, US averages push towards 20%, with subprime products breaching 30%. The divergence is not merely academic — it signals two fundamentally different worlds of financial exposure.

You can see the scale of the problem most clearly in the graph tracking credit card interest rates. It shows two lines moving in entirely different directions. In Europe, interest on overdrafts stays fairly steady at around 8%. In the US, the line climbs and climbs — hitting around 20% on average, and soaring past 30% for people with weaker credit scores.

Put plainly: Europe’s borrowing costs sit on a gentle hill. America’s look like a mountain range.

Figure 1 – Credit card interest rates from June 2010 to February 2023. Data sources: U.S. national average and bad-credit rates from Dilworth & Tang (2023); euro-area rates from Knops & Fromm (2022)

This matters because digital payments blur the line between paying and borrowing. When a tap can instantly become an overdraft, the poorest pay the highest price. In the United States, where around one in five citizens is unbanked or underbanked, the cost of participation in a cashless system becomes a form of structural punishment. Those with the least pay the most to access the basics of modern economic life.

Europe tells a more complex story. Bank account access is almost universal, but the infrastructure behind digital payments is anything but sovereign. Cross-border transactions inside the Eurozone rely overwhelmingly on the machinery of US giants — Visa, Mastercard, PayPal — whose profitability rests precisely on the dynamics that have fuelled inequality elsewhere. European consumers may enjoy lower fees, but they are dependent on corporate networks whose incentives sit oceans away.

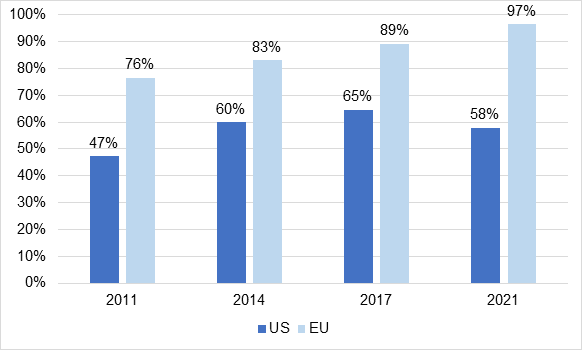

The graph (2) comparing bank account ownership among people with low levels of education shows another fissure: in the US, exclusion rises sharply among poorer and less-educated groups; in Europe, the slope is gentler but still present. Beneath the surface of digital optimism is an old story — systems designed without the margins in mind inevitably replicate the inequalities of the societies beneath them.

Figure 2: Bank account ownership among adults with primary education or less: Comparison between the United States and the euro area. Source: World Bank (2022); authors’ calculations.

Governments have begun to stir. The Biden administration’s move to restrict excessive overdraft fees is one small correction. In the EU, the proposal for a Digital Euro hints at a public alternative to the dominance of private rails. But none of these efforts replace the role of cash as the only payment instrument that guarantees universal access, no questions asked, no data extracted, no fees lurking in the shadows.

What the evidence shows — graph after graph, dataset after dataset — is not that digital payments are inherently harmful, but that their current architecture is. When essential economic functions depend on private credit systems, social hierarchies harden. And when cash disappears, so does the one form of payment that refuses to discriminate.

Cash was never just a method. It was, and remains, the floor beneath the system — a guarantee that participation in society is not conditional on profitability. In a moment when financial exclusion is increasingly digital, that guarantee is more than a convenience. It is a democratic necessity.